As the 22nd FIFA World Cup finals reach their decisive latter stages, we present LGC Industrial’s own metallurgic spin on the tournament – a fun- and fact-filled look at the science and stories behind the coveted trophies.

The original trophy: Jules Rimet

The first World Cup – known as the Jules Rimet trophy – was made of gold-plated sterling silver on a lapis lazuli base. Inspired by a statue at the Louvre Museum in Paris, it featured the figure of Nike, the Greek Goddess of Victory, weighed 3.8 kg and was 35cm high. First won by Uruguay in 1930, the original trophy spent World War Two in hiding in Italy amid fears that the Nazis would try to loot it.

Queen Elizabeth II presents the Jules Rimet trophy to England captain, Bobby Moore

Credit National Media Museum/wiki commons

The first replacement

Brazil won its third World Cup tournament in 1970, and as a result got to keep the Jules Rimet version permanently. Since then, teams have competed for the more prosaically-named, but still iconic, FIFA World Cup Trophy – featuring two human figures holding the Earth in their hands. Standing 36.5cm tall on its malachite base and weighing 6.17kg, the golden trophy is believed to be hollow since – as one scientist pointed out – a solid version would weigh about 70kg and thus be too heavy to raise aloft (not to mention “a big waste of gold”).

A habit of going missing

Four months before the 1966 tournament in England, the Jules Rimet trophy was stolen while on public exhibition at Westminster Central Hall. It was later found by an improbable hero – a mongrel Collie dog called Pickles – wrapped in newspaper and hidden under a car in Beulah Hill, South London. Pickles was rewarded for his detective work with a silver medal from the National Canine Defence League, a lifetime supply of dog food, and an invitation to the victorious England team’s celebratory banquet that summer.

At the following tournament, Mexico 1970, the winning Brazilian team somehow lost the top of the trophy during their post-final celebrations, meaning that reserve player Davio had to retrieve it from a young spectator at the stadium exit - and that the next version of the trophy was designed without detachable parts.

In 1983, however, Jules Rimet’s luck finally ran out when thieves crowbarred open the cabinet it was stored in, at the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) HQ in Rio de Janeiro. The iconic cup has never been recovered, and is widely believed to have been melted down - although a replica was later donated to the CBF by Kodak of Brazil.

Real or fake? Science solves the mystery…

Shaken by the 1966 theft, the English Football Association made a secret replica of the Jules Rimet trophy – primarily from base metals – for use at official functions. As FIFA had explicitly forbidden copying, the replica spent several years hidden under its creator’s bed - but when it was eventually sold at auction in 1997, it was FIFA who bought it, for £254,000.

The high price paid also led to rumours that FIFA had actually purchased the original Jules Rimet trophy instead of the replica – a notion that was only dispelled by scientists at the University of Manchester in 2016. Using a state-of-the-art CT scanner, they produced a virtual model that detected no trace of the silver used in the real trophy, but strong signals for tin and lead. The object – which is now on display at the National Football Museum in Manchester, England – was definitely a fake.

A new ‘trophy’ every four years

After Brazil retained – and eventually mislaid – the Jules Rimet version, FIFA changed its rules to ensure that no country can again keep the World Cup trophy outright. Although it briefly hands the real FIFA World Cup Trophy - remember - the one with the humans holding up the world? - over to the winning team after the final, it keeps that version mostly under lock and key at its Zurich headquarters. This means the bauble that winning teams get to take home after every World Cup is yet another replica - this time a gilt and brass copy of the FIFA World Cup Trophy known as the World Cup Winners’ Trophy. One of these copies is produced for every tournament – using a moulding, die grinding and chiselling process to obtain an exact copy, followed by polishing, ultrasonic cleaning, gilding, washing and varnishing. It’s a process almost as long and exhaustive as the history of the World Cup trophies themselves.

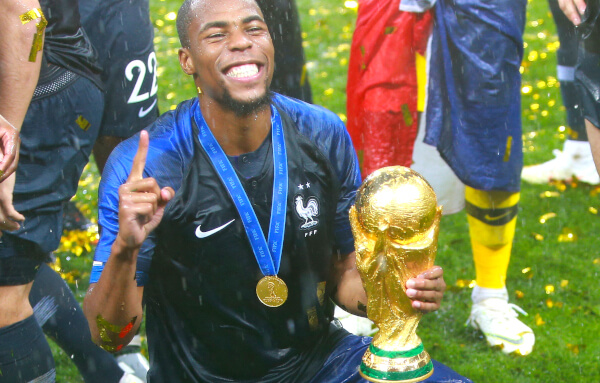

France’s Djibril Sidibe with the FIFA World Cup Trophy in 2018

Credit: soccer.ru/wiki commons

LGC Industrial – The Material Difference

Analysing metals throughout the production cycle is imperative to ensure that they are safe and reliable for use. We offer metal alloy CRMs ranging from aluminium to zinc, allowing you to source the exact testing products you need. To hear more about our product offering or to request a quote please contact us. Meanwhile, stay up-to-date on products, catalogues, whitepapers, and more by following us on LinkedIn and Twitter.